Women are more likely to inherit brain structures linked to depression from their mothers than their fathers

Published online 30 March 2017

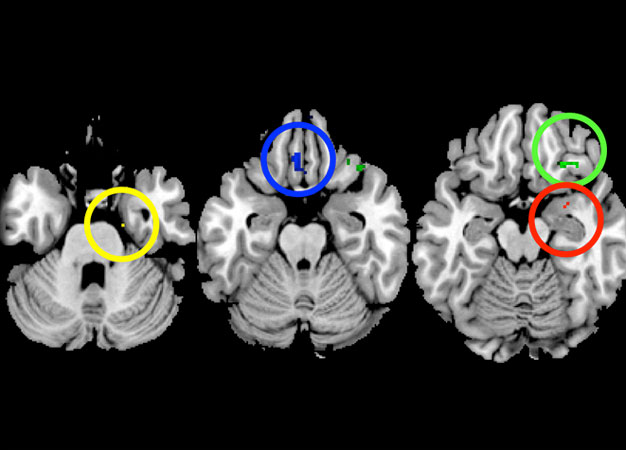

Mother-daughter similarities in the brain are most pronounced in regions involved in controlling emotion: the amygdala (red), gyrus rectus (blue), orbitofrontal cortex (green), parahippocampus gyrus (yellow), and anterior cingulate cortex.

Reproduced, with permission, from Ref. 1 © 2016 B. Yamagata et al.

A brain-imaging study by neuroscientists at Keio University School of Medicine begins to explain the close association between depression in mothers and teenage daughters1.

Scans revealed that the size of the brain area controlling mood and emotion correlated more between mothers and daughters than between mothers and sons, or between fathers and children of either gender.

If a parent has a family member with a mood disorder, there is approximately a 40 per cent chance that his or her offspring will develop that psychiatric condition, and the risk is even greater for mothers passing on their family's mental illness to daughters. As such, the insights gleaned through brain imaging can help answer critical questions about maternal effects on brain development and female susceptibility to developing depression and other female-biased psychiatric disorders, says Bun Yamagata, the study's lead author, who is now an assistant professor at Keio University's Department of Neuropsychiatry.

While working as a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University in the United States, Yamagata collaborated with Fumiko Hoeft, who holds a joint appointment at Keio University, to study the heritability of brain circuitry. They recruited 35 healthy families from California and placed the parents and their biological children in a magnetic resonance imaging machine.

Their analysis showed that the volume of gray matter in the brain's amygdala, hippocampus and other parts of the so-called corticolimbic circuit, which plays a critical role in mood disorders like depression, correlated most strongly in mother-daughter pairs than in other parent-offspring relationships.

The reason remains unclear, but Yamagata speculates that genetic, prenatal and postnatal environmental factors and their interactions may underlie the intergenerational patterns.

To tease out those contributors, Hoeft and her colleagues are now repeating the experiment with mothers who used donor eggs, families that used other women to carry their genetic offspring to term, and, as controls, mothers whose eggs were fertilized using assisted reproductive technology. The research, Hoeft says, "will establish a new and complementary paradigm for noninvasively studying genetic and environmental influences of the human brain."

Meanwhile, Yamagata is running similar brain-scanning experiments at Keio University with families in which the parents have been clinically diagnosed with depression. He hopes the study will offer further justification for early interventions in female mental health.

Understanding how psychiatric diseases persist from one generation to the other can help to develop novel therapeutics and prevention paradigms that target high-risk individuals such as women, says Yamagata.

Reference

- Yamagata, B., Murayama, K., Black, J. M., Hancock, R., Mimura, M., Yang, T. T., Reiss, A. L. & Hoeft, F. Female-specific intergenerational transmission patterns of the human corticolimbic circuitry. Journal of Neuroscience 36,1254-1260 (2016). | article