Biobank of colorectal cancer 'organoids' reveals cancer's secrets

Published online 25 August 2016

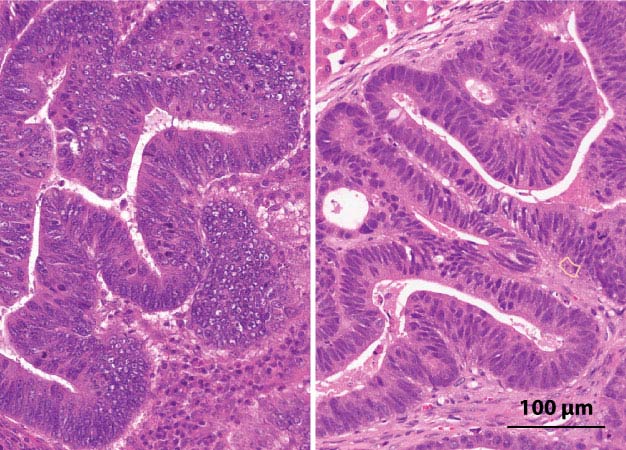

Three-dimensional tumors grown on a dish and transplanted into animal models (right) develop similar cellular structures as the original colorectal cancer cells taken from patient tumors (left).

Reprinted from Ref. 1, Copyright 2016, with permission from Elsevier.

Three-dimensional tumors grown from cells of colorectal cancer patients are being used by Japanese researchers to explore how benign tumors transform into malignant metastatic cancer that claims nearly 700,000 lives around the world each year.

Their library of 'organoids' offers a unique opportunity to observe colorectal cancers as they would behave inside the human body.

"Until recently, cell lines and rodents have been the only living tools for cancer research, but these models may not fully reflect the characteristics of the clinical cancers. This has caused a bottleneck in translation from basic science to clinics," says Toshiro Sato of the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Keio University School of Medicine, who led the study.

Colorectal cancer organoids are clusters of cells that form a mini-tumor, with the same structural features as the original tumor.

To build the library, Sato and colleagues collected cells from 52 tumors in 43 patients with colorectal cancer, including a number of rare subtypes. These samples were cultured with factors that might activate or repress particular signaling pathways known to affect cell growth. Each tumor sample thrived under a unique 'niche factor' microenvironment.

The result was a library of 55 colorectal cancer organoids, each with the same molecular signature as its in-vivo counterpart. They also replicated the same cellular structure when transplanted into an animal model (see image)1.

The biobank has already provided some valuable insights into colorectal cancer growth and metastasis. For example, because the team tailored the niche factors to each tumor, they were able to see which niche factors the tumors needed for growth, and which ones they didn't require.

While healthy intestinal stem cells are dependent on certain niche signals to grow, the researchers noted that tumors appear to have negated some of these growth restrictions through genetic mutations.

"We referred to this phenomenon as niche-independent growth," says Sato. "By profiling the niche factor requirements of each tumor organoid, we found that the transition from a benign adenoma to cancer, frequently accompanies this loss of niche-dependency." Interestingly, this same process did not appear to influence the transition from early cancer to advanced metastatic cancer.

The study showed that while samples from the original tumor and from its metastases were almost identical genetically, the metastatic organoids were still much more likely to metastasize when transplanted into the animal model.

This suggests some other mechanism, unrelated to genetic mutation is causing cancers to spread; a mechanism that we are yet to identify and target with treatment.

Reference

- Fujii, M. et al. A colorectal tumor organoid library demonstrates progressive loss of niche factor requirements during tumorigenesis. Cell Stem Cell 18, 827-838 (2016). | article