A molecular process crucial to the postnatal development of the retina is uncovered by an international team of researchers

Published online 6 March 2015

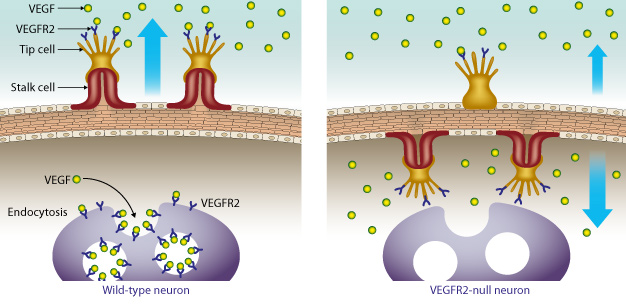

A growth receptor called vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) prevents over-vascularization of retinal neurons by binding excess VEGF. In mouse models that do not express the VEGFR2 receptor in their retinal neurons, the vessels grow inward toward the neurons instead of outward.

Reproduced, with permission, from Ref. 1 © 2014 Elsevier

A key molecular process governing the healthy development of the eye in mice has been uncovered by researchers at Keio University, along with international collaborators. Their unexpected findings may inform new treatments for eye diseases1.

The eyes are a good example of the essential role played by complex interactions between the central nervous system and the blood and lymph vessel networks that ensure the healthy development of the body after birth. Without the correct development of the retina, signals sent via neurons to the central nervous system would be disrupted, potentially affecting our ability for sight.

The growth, pattern and distribution of blood vessels in the body is regulated by a signaling protein called vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). New blood vessels emerge from pre-existing vessels when VEGF activates receptors present in endothelial cells that line all of the veins in the body ― a process called angiogenesis.

Yoshiaki Kubota and co-workers at Keio University, together with scientists from across Japan, the United States, and Australia, made a surprising discovery when they set out to investigate angiogenesis in the development of the eye, and in particular the retina, after birth.

"Most researchers are focusing on the signaling and function of a VEGF receptor called VEGFR2 in endothelial cells," says Kubota. "However, to our surprise we discovered that VEGFR2 is much more abundantly expressed in neurons than in endothelial cells in mouse retinas."

This initial discovery enticed the researchers to examine why VEGFR2 was so strongly expressed in retinal neurons. The team painstakingly generated multiple lines of mice with the Vegfr2 gene deleted from their retinal neurons. They found that the absence of neuronal VEGFR2 in the retina led to misdirected angiogenesis ― instead of sprouting new vessels outward, the vessels began to grow inward toward the neurons themselves (see image). This caused unusually dense vascular growth around the retinal neurons.

"VEGFR2 essentially acts as a barrier, binding VEGF and therefore preventing excess vessel growth in the retina," explains Kubota. "This process ensures that the eye receives the appropriate level of vascular supply and prevents over-vascularization."

Further analysis is required to determine if a lack of VEGFR2 receptors in the retina could have an impact on eye diseases such as diabetic retinopathy.

"We also hope that this unprecedented mode of VEGF regulation may help to uncover strategies for targeting human diseases related to excess vessel growth, such as cancer and rheumatoid arthritis," says Kubota.

Reference

- Okabe, K. et al. Neurons limit angiogenesis by titrating VEGF in retina. Cell 159, 584-596 (2014). | article