Japanese researchers are engineering the technology and rules of superhuman sports, just in time for the Tokyo Olympics

Published online 6 March 2015

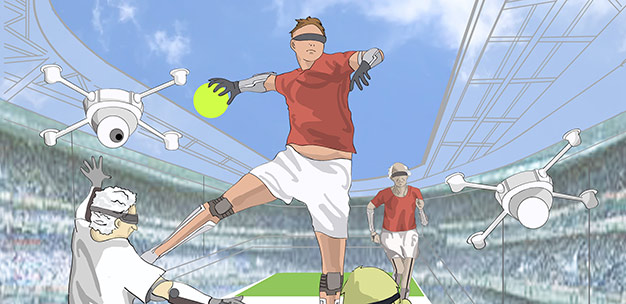

The Superhuman Sports Committee is developing technologies that can enable individuals of varying physical ability, including the elderly, to compete in sports events.

© 2014 Keio University

The famous victory of supercomputer Deep Blue over world chess champion Garry Kasparov in 1997 proved that machines were beginning to challenge the intellectual ability of humans. Kasparov soon turned his digital adversaries into allies, introducing Advanced Chess in which human players compete with the assistance of computer programs. These hybrid teams have defeated even the most advanced supercomputers.

At Keio University's Graduate School of Media Design, human augmentation and virtual-reality researcher Masahiko Inami is now applying this concept of transhumanism ― using technology to enhance the human condition ― to the physical arena.

"Man-machine integrated systems will become the strongest systems in the world," asserts Inami. In 2014, soon after the announcement of the Tokyo Olympics, he brought together a group of researchers, sports psychologists, video game designers and magicians to form the Superhuman Sports Committee, which aims to encourage the development of human-machine integrated systems to transform the experience of sport for players, trainers and audience alike.

In the lead-up to the 2020 Olympic Games, the committee plans to test the functionality, strength and entertainment value of such integrated systems in a series of public annual competitions.

Spider vision and flying balls

As a high school student, Inami was fascinated with the technology culture embodied by technology-inspired anime and Tokyo's electronics wonderland of Akihabara. "I visited Akihabara almost every day," says Inami, who would go exploring with his friends and sometimes purchase used computer parts or electronic circuits. Later as an undergraduate, he built small robots and virtual reality equipment, including a mechanical arm that could serve beer perfectly. During his doctorate, inspired by the manga and film series Ghost in the Shell, Inami developed an 'invisibility cloak' that used projection-based technology and a special retroreflective material to optically camouflage objects.

Now a professor at Keio University, Inami is continuing these projects through the Superhuman Sports Committee. His team is developing tactile communication systems that can convey to audiences what it feels like to hit a tennis ball traveling over 200 kilometers an hour back over the net. Using liquid-crystal goggles, the crowd can get a clearer view of the ball's fuzzy surface as it speeds across the court. Inami's team is also developing a way to mimic the vision of spiders, to give players a 360-degree field of view through head-mounted displays.

Another member of the committee, Jun Rekimoto at the University of Tokyo has designed what he calls a Flying Head, in which a camera attached to a floating drone can follow athletes across the court and send real-time footage of their movements from a third-person perspective via a head-mounted device. This device could be used to train basketball players the way that wall-to-wall mirrors give dancers and gymnasts perspective. Rekimoto's team has also designed a drone-powered ball that evokes scenes from quidditch matches in Harry Potter.

More accessible sports

These technologies will force sports engineers to modify the rules of existing sports or invent entirely new sports, says Inami. Exoskeleton suits that can make sprinters run several orders of magnitude faster, for example, could make speed the lesser challenge. "Running fast is not so hard, but stopping safely is difficult." Perhaps the 100-meter dash could be made into a start-and-stop test, where runners are required to end the race exactly on the finish line.

"Technology can also balance out differences in physical ability, for example due to age or disability," adds Inami, who foresees the emergence of more athletes like the German champion long-jumper and amputee Markus Rehm who beat able-bodied competitors at the German Athletics Championships in Ulm last year with a leap of 8.24 meters. Officials from Germany's track-and-field governing body raised questions as to whether Rehm's carbon-fiber prosthetic leg gave him an unfair advantage. Superhuman sports are likely to see such situations abound, says Inami. "World records in the Paralympics could soon surpass those of the Olympics."