Combing the epidermis for clues, Keio researchers found that hair follicles are critical gateways in the fight against infection

Published online 6 March 2015

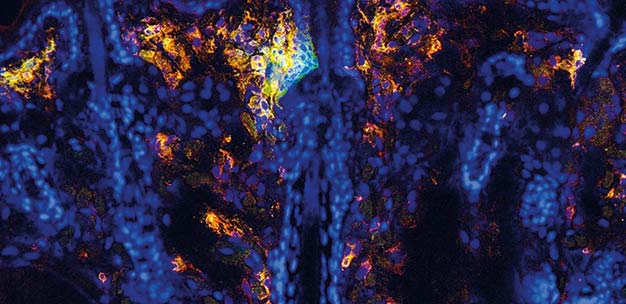

Skin dendritic cells (orange and green) accumulate around hair follicles (blue nuclear staining) in mice.

© 2015 Masayuki Amagai, Keio University

Hair follicles function as entry points to the outer layer of skin for cells that protect against infections, Keisuke Nagao and his team from the Department of Dermatology, Keio University School of Medicine, reported in 20121. The cells in question are members of a specialized class of white blood cells known as Langerhans cells. They form part of the first line of defense in the body's fight against infections, sampling antigens in the epidermis and transporting them to the lymph nodes.

When Nagao first proposed exploring how populations of Langerhans cells are maintained and replenished in the epidermis, Masayuki Amagai, the chair of the Department of Dermatology, was initially very hesitant. "I felt that the question was too fundamental for dermatologists to pursue," he recalls. But after five years of investigation, Nagao was able to discover that the precursors of Langerhans cells enter the skin via hair follicles ― a very surprising finding that no one had predicted. "Nagao answered the question beautifully," says Amagai.

The researchers captured images of mouse skin showing Langerhans cells clustering around hair follicles in skin that was depleted of Langerhans cells (see image). The images clearly showed that colonies of Langerhans cells form around hair follicles, but as they were only snapshots in time, the researchers could not tell whether the cells were being produced at the follicles or recruited from elsewhere.

Nagao's team then used two-photon electron microscopy to obtain videos that showed white blood cells, including Langerhans cells, congregating around hair follicles within 30 minutes to 4.5 hours of applying stress to the skin. The videos also revealed cells entering hair follicles and migrating upward to repopulate the epidermis. "When we saw these movies, we were astonished," Amagai says.

The Keio team went on to find further evidence of the important role of hair follicles in Langerhans cell repopulation. For example, mice that are unable to produce hair follicles show limited repopulation of Langerhans cells after depletion, while human patients with autoimmune disorders that result in the destruction of hair follicles show a similar absence of Langerhans cells. Furthermore, they found that Langerhans cells repopulate the hairless paws of normal mice by migrating from adjacent hairy regions. The team also showed that intercellular signaling proteins known as chemokines are involved in attracting Langerhans cell precursors to hair follicles.

Since its publication two and a half years ago, the paper has been highly cited in the scientific literature ― 57 times according to Google Scholar ― and has been ranked in the 90th percentile for articles published around the same time in Nature Immunology.

The findings have forced scientists to re-evaluate the importance of hair follicles ― they are no longer considered merely sites of hair growth; they are now thought of as being important gateways in the body's immune response, Amagai says. The findings also raise the question of whether hair follicles function as conduits between the dermis and the epidermis for other cells and substances. Hair may turn out to be even more critical than even Nagao's research suggests.

Reference

-

Nagao, K. et al. Stress-induced production of chemokines by hair follicles regulates the trafficking of dendritic cells in skin. Nature Immunology 13, 744-752 (2012). | article